| Catalog | Past Items | Order Info | Terms/Conditions | About Us | Inventory Clearance |

As Colt worked with U.S. Ordnance Department for military contracts in 1860-61 he needed to keep his business profitable. To do so, he took advantage of the huge demand from the Southern States, just then expecting to be invaded at any time and desirous of obtaining any weapon better than a pitchfork they were clamoring for a chance to purchase such a fine weapon as Colt produced.

Some of his first shipments of the 1860 Cavalry Model went to known dealers in the Southern States. These sales were completely legal, because the South had yet to secede. Colt’s motives were unquestionable; he was driven by profit rather than a desire to help the South.

Known shipments of the Model 1860 Armies (approximately 2,230) were made to a number of Southern dealers between December 1860 and April 1861, as follows: December 27, 1860, 300 to Gov. Wm. Brown of Georgia; January 15, 1861, 50 to Wm. Sage, Charleston, South Carolina; 160 to Wm. Martin, Natchez, Mississippi; 240 to H.D. Norton & Bros, (prior to April 16th), San Antonio, Texas; and 1,100 to Kitteridge & Folsom (up to April 9th), New Orleans, Louisiana. Colt even continued after the firing on Sumter, shipping Peters, Williams & Company, in Richmond, Virginia 500 on April 15, 1861, three days after the firing started and long after the Southern States had seceded.

In addition to the above, Colt sent 1,000 New Model Fluted Army Revolvers to Texas at the behest of his friend Ben McCulloch and the aid of Senator Louis T. Wigfall, who would later command the 1st Texas Regiment and still later the Texas Brigade. Wigfall had been instrumental in acquiring the revolvers and it is likely that Colonel Key received his revolver serial number 3575, from Wigfall, either by purchase or presentation. The first 250 revolvers of the McCulloch order were shipped on March 28th, and the following 750 on April 9, 1861. No factory letter for SN 3575 survives, but among the serial numbers known to have been in the McCulloch shipment of 1,000 were SN 3449 and SN 4381. This leaves little doubt that SN 3575, which is inscribed "John C.G. Key” on the backstrap, arrived in Texas as part of the McCulloch order. The grip stock of serial number 3575 is heavily stained with blood. It was so drenched with blood that it ran between the backstrap and the grip staining the inside of the grip. And there lies a story.

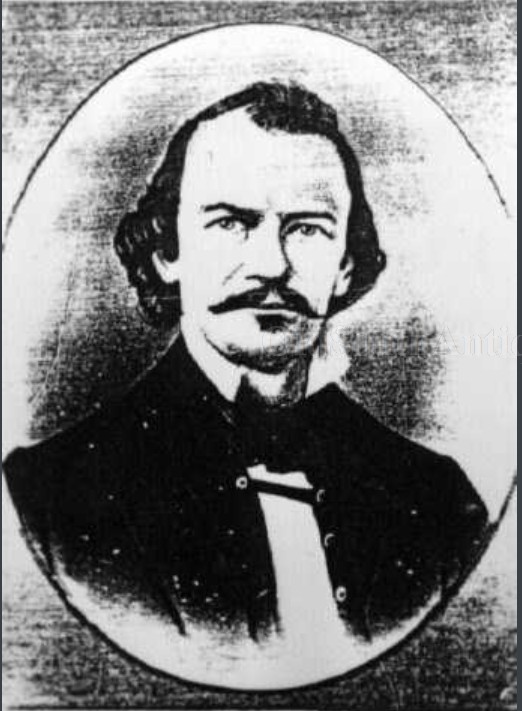

John Cotlett Garrett Key was born a South Carolinian in the year 1809 and died a Texan in 1866. When the War Between the States broke out he was a successful lawyer in Gonzales, Texas. John C.G. Key organized a company of infantry, the "Hardeman Rifles," officially enrolling them on July 11, 1861 at Camp Clark Guadeloupe County, Texas. Key boarded the Hardeman Rifles on the steamer "Florida” at Beaumont and sailed for Virginia immediately afterwards. In Richmond the Rifles became Company A, Fourth Texas Infantry Regiment under Colonel Robert Allen, with John Key as Captain. Colonel Allen was literally driven from the camp by the independent minded Texans who were fed up with his harsh discipline. Allen was replaced as commander of the 4th Texas by Colonel John Bell Hood.

The 4thwas brigaded with the 1st and 5th Texas under Brigadier General (ex U.S. Senator) Louis T. Wigfall. The Texas Brigade wintered at Dumfries, Virginia. Upon Wigfall’s resignation to take his place in the Confederate Senate, Colonel J. B. Hood was promoted to brigade command on March 3rd, and John C.G. Key was made Major of the Regiment.

At the Battle of Gaines Mill General Hood took personal command of his old outfit, the 4thTexas. He knew his men, he had once boasted that he could "double-quick the 4th Texas to the gates of hell and never break the line”[1] At Gaines Mill he proved it. The Fourth Texas started the charge in reserve, but the overly aggressive Hood led the just as aggressive Fourth Texas to the front and it is well that he did; the 4thTexas, under Hood’s personal leadership is credited with breaking the Yankee line. The Fourth Texas drove them up and over the top of Turkey Hill, where they were immediately greeted by canister from Federal artillery posted on their left. Hood faced them to the left and ordered another charge. Supported by the Eighteenth Georgia, the Fourth Texas charged the guns and captured fourteen of the eighteen pieces, thus ending the threat to Richmond.

Now Hood turned his attention to the casualties. He spent the night supervising the treatment and removal of the wounded and was struck by the heavy losses. Years later a staff officer remembered Hood sitting on a cracker box, "Just look here, Major,” Hood wept, "at these dead and suffering men, and every one of them as good as I am, and yet I am untouched.”[2] Major Key was among those severely wounded in the charge. As the Fourth Texas formed for roll call the next morning General Hood rode up to his old command and asked: "Is this the 4th Texas?” "This is all that remains,'' was the answer. Hood turned his horse in a vain attempt to hide his tears. Of all Hood's regiments, the Fourth Texas had suffered the most at Gaines Mill. Their casualties numbered 44 killed, 208 wounded, and 1 missing, which were nearly half the losses in his entire brigade. Half of all the enlisted men and all of the field-grade officers were casualties.[3]

The Texas Brigade was now arguably the most famous brigade in the Army of Northern Virginia, primarily because of their performance at Gaines Mill, where they marched over the backs of the Confederate troops that had gone before, crossed Boatswain’s Creek and drove Fitz John Porter’s Yankees out of their prepared works at the point of the bayonet. Such bravery was costly; the Fourth’s leadership was decapitated. Colonel Marshall and Lieutenant Colonel Warwick were killed and Major Key was wounded and out of action. But the Texans held Turkey Hill, and Richmond was saved for another day.

To fill Hood’s shoes in the eyes of the 4th Texas was a herculean task, but Key had been under Hood’s own eye at Gaines Mill and so sure was he that Major Key was the man for the place, the position was held open for him during an active campaign in which he could not participate due to wounds.

Colonel Key missed the Battle of Second Manassas due to his wound (or wounds). He caught up with his regiment in time to ably command it at South Mountain on September 14th, but he was not sufficiently recovered to continue in the field the following day and was unable to command at Sharpsburg. The Colonel commanded through the winter, but his regiment was little engaged during the Fredericksburg Battle. In the spring the 4th along with the rest of Hood’s Division was sent to Suffolk, Virginia to aid a supply gathering mission, not returning until after Chancellorsville had been fought.

When the Army of Northern Virginia marched north on the campaign to end the War, Colonel Key and the 4th Texas were once again in fighting trim and high spirits. The authorities in Richmond had pronounced him a gallant and skilled warrior, but what was John C.G. Key the man like? Because he died in 1866 he never wrote a memoir or letters to the Confederate Veteran Magazine of the sort that has given us insight into so many of the prominent leaders of the Confederate Armies. I was able to find one tidbit not related to battle, written by J.B. Polley, the author of the "Charming Nellie Letters”. Polley kept his fine sense of humor even after the disappointment of the Gettysburg Campaign. Writing on July 30, 1863 he describes the march into the North: "Crossing the Potomac on a pontoon bridge, at noon we halted in the outskirts of the town of Williamsport, Md. and, mirabile dictu (spoken miracles) drew rations of whiskey. (it had been pouring rain) There was only about a gill to the man, but as the temperance fellows gave their shares to friends, the quantity available was amply sufficient to put fully half the brigade not only in a boisterously good humor, but in such physical condition that the breadth of the road over which they marched that evening was more of an obstacle to rapid progress than its length. At an early hour, John Brantley, of my company, became so exhausted by his latitudinarian tendencies as to prefer riding to walking, and perceiving that Col. Key was in an excellently good natured condition, took advantage of a momentary halt to approach that gallant officer and slapping him familiarly on the leg, remarked: "Say, Kunnel! I’m jus’ plum’ broke down; can’t you walk some an’ lemme ride a while?”

Bending forward over his horses neck and grasping the pommel of his saddle with both hands to steady himself, the old Colonel looked pityingly down at Brantley and, between hiccoughs, replied: "I’d do it in a minute, ole feller, d—d if I wouldn’t but I’m tired as h--- myself, ah sittin’ up here an’ah hol’in’on.”

This short story by Polley gives us a pretty good insight into the Colonel’s jovial character. Little did he know that shortly he would not be able to walk or how near was his last ride.

At 2:00 A.M. July 2nd, the 4th Texas was at Cashtown; in the next two hours Colonel Key marched them the eight miles to Gettysburg and had them cooking breakfast along Willoughby Run. But time was frittered away and Longstreet’s Corps was not deployed for attack until after 4:00 P.M. Artillery posted at Devil’s Den and the Peach Orchard roared a greeting of shell which struck down fifteen of the 4th Texas just as Colonel John Key ordered the charge. General Hood was disabled almost at the same time by another shell. General Evander Law now took over the Texas Brigade as they drove the Federals before them through Devil’s Den and advanced into the iron storm, splashed across Plum Run, and turned up the "valley of death” driving towards the stone wall at the base of Little Round Top.

The destructive artillery fire was joined by Major Homer Stoughton’s 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters, armed with .52-caliber breech loading rifles and General Strong Vincent’s Federals at the top of the hill. The 2nd was securely ensconced behind the stone wall at the base of the hill. Though well protected and wielding rapid firing breech loading rifles, they still could not stop the advance of the Texans. They did however make them pay a steep price for that little bit of rock wall. Colonel John C.G. Key and Lt. Colonel Benjamin Carter were both shot down at the wall.[4] Lt. Colonel Carter was wounded in the face, arm and leg and lay dying and according to Major John P. Bane, Colonel Key was severely wounded while "gallantly urging the men to the front.” The remaining Texans pushed on, driving the Yanks back to Little Round Top. Try as they might, the Texans could push them no farther.

After the fighting had moved beyond the wall, Colonels Key and Carter were removed to a field hospital where they suffered untold agonies while the battle raged for another day. On the following night Colonels Key and Carter were placed together in a wagon for the torturous ride back to Virginia. Colonel Carter suffered so grievously he was eventually left at the George Farm near New Franklin. Colonel Key endured the trip but never recovered. After nearly a year trying to regain his health, he applied for retirement on April 27, 1864, which was approved by the surgeon on November 1, 1864 and forwarded to the Assistant Adjutant General. But on November 5, 1864 while convalescing in Edgefield, South Carolina he was reassigned from the Invalid Corps to the Reserve Forces of the State of Mississippi, while noting he was unfit for duty and directing that he report when his health would permit.

There is no indication that Colonel Key was ever again able to report for duty. Having died in 1866 as a result of the effects of the War, he ended his war where he had begun it; in Gonzales. He is buried in the Masonic Cemetery there. Colonel John C. G. Key led the 4thTexas, a regiment readily acknowledged to have been one of the bravest and most hard charging in the Army of Northern Virginia and one to which General Lee often turned when he was most pressed. Two of the most famous charges of the War are claimed by the 4th Texas under his leadership; Gaines Mill and Devil’s Den. In both of these charges Colonel John Key was severely wounded; the last leading to his early death. Ironically his early death has caused him to be nearly forgotten, though his grave stone does acknowledge his service to the Confederacy as Colonel of the 4th Texas.

Now, a hundred and fifty odd years later the Colt revolver that he carried in these battles is bringing him some well-deserved appreciation and as long as mankind admires men of a greater mold, collectors will recount his deeds of daring and "wish this one could talk”. Maybe it does if you listen carefully.

The revolver is in excellent condition and completely original with the exception of the wedge. All serial numbers match, the action works perfectly, the rifling is excellent, the metal smooth, with traces of blue. Grips are badly stained with blood. This is a rare combination of one of the most desirable handguns from the War, carried by the Colonel of one of the most famous regiments of the War, who was wounded in two of the most famous charges of the War.

[1] The Gates of Richmond, by Sears

[2] John Bell Hood and the War for Southern Independence, McMurray

[3] http://www.pha.jhu.edu/~dag/4thtex/history/history.html

[4] Texans at Gettysburg

Copyright © 2025 OldSouthAntiques.com All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Powered by Web-Cat Copyright © 1996-2025 GrayCat Systems